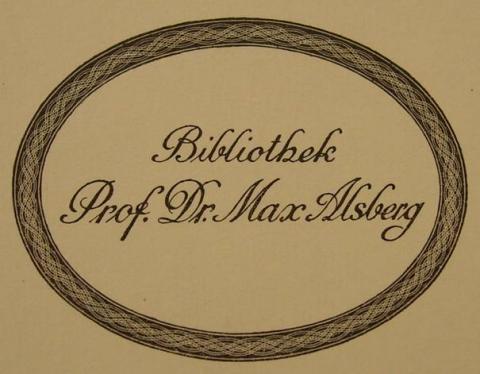

During the Weimar Republic, the defence lawyer and legal scholar Max Alsberg, who moved to Berlin in 1906, had an office at Nollendorfplatz 1 together with Kurt Peschke, Kurt Gollnick and Lothar Welt. When, as a Jew, he was banned from working in July 1933, he escaped to Switzerland, where he committed suicide on 11 September 1933. His widow Ellinor (née Sternberg, widowed Alsberg, later Böhm, 1888–1965), who remained in Berlin until 18 February 1934 before escaping to Switzerland, appointed the Berlin asset manager Friedrich Daerneborg to represent her interests in liquidating the contents of the huge villa in the Grunewald district of Berlin and in dealing subsequently until 1941 with her many other affairs. Daerneborg drew up a 74-page list of all artworks and household objects and the large library. One part of the law library in the basement alone consisted of twenty large crates of books, which were to be shipped to Britain in 1939. While the majority of Alsberg's extensive collection of valuable sculptures, ceramics, furniture, paintings and tapestries (212 lots altogether) were auctioned in January 1934 by the auctioneer Paul Graupe, who was himself later to be persecuted, other household items were auctioned with the approval of the Devisenstelle (Foreign Exchange Office) by the Berlin auctioneers Rudolph Lepke's Kunst-Auctions-Haus and Auktionshaus Goldschmidt & Co. Excluded from this list were objects that Daerneborg himself had hitherto given to friends or employees or sold on his own account. He also sold two unidentified vehicles, a Rolls Royce and a Goliath. Ellinor Alsberg fled to Britain in 1939, her removal goods having been stored by the Berlin transporter Spedition Knauer in Basel and by N.V. Koninklijke Meubeltransport-Maatschappij De Gruijter & Co. in The Hague. In April 1941 these goods were seized in the Netherlands by the recently established Nazi Sammelverwaltung feindlicher Hausgeräte (Joint Administration of Enemy Household Appliances). With her children Renate and Klaus (later Claude G. Allen, New York) she received compensation after 1945 under the German Federal Restitution Act, which took account not of the artworks or books but merely of real property, securities and special levies. In 2007 the Restitutiecommissie der Niederlande recommended the return of a valuable eighteenth-century carpet, which had turned up in 1948 at an art dealership in Hamburg. A historical print in the library of the Österreichische Galerie acquired in 1961 by Marlborough London has the ex libris Max Alsberg, but for lack of further details the Art Restitution Advisory Board failed to recommend its restitution. The whereabouts of the auctioned and seized art and cultural objects from Max Alsberg's collection have not been clarified to date.

Max Alsberg

Beschluss des Kunstrückgabebeirats, Bibliothek der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, 15.5.2014, URL: www.provenienzforschung.gv.at/beiratsbeschluesse/Bibliothek_Oesterreichische_Galerie_Belvedere_2014-05-15.pdf (3.12.2020).

Restitutiecommissie, Recommendation regarding the application for the restitution of an eighteenth-century Savonnerie carpet (NK 1066), 16.4.2007, URL: www.restitutiecommissie.nl/en/recommendations/recommendation_158.html (3.12.2020).

Paul Graupe (Hg.), Kunstbesitz Prof. Max Alsberg †, Berlin – Gemälde und Kunstgewerbe aus einer bekannten süddeutschen Privatsammlung – Verschiedener Berliner Privatbesitz. Versteigerung 131, 29.–30.1.1934, Berlin 1934, URL: doi.org/10.11588/diglit.6198.

Alexander Ignor, Max Alsberg (1877–1933) "Unter den wissenschaftlich arbeitenden strafrechtlichen Praktikern weitaus an erster Stelle", in: Stefan Grundmann/Michael Kloepfer/Christoph G. Paulus (Hg.), Festschrift 200 Jahre Juristische Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Geschichte, Gegenwart und Zukunft, Berlin 2010, 655–682.

Gerhard Jungfer, Max Alsberg. Verteidigung als ethische Mission, in: Kritische Justiz (Hg.), Streitbare Juristen. Eine andere Tradition, Baden-Baden 1988, 141–151.

Tillmann Krach, Max Alsberg (1877–1933). Der Kritizismus des Verteidigers als schöpferisches Prinzip der Wahrheitsfindung, in: Helmut Heinrichs (Hg.), Deutsche Juristen jüdischer Herkunft, München 1993, 655–666.

Simone Ladwig-Winters, Rechtsanwaltkammer Berlin (Hg.), Anwalt ohne Recht. Das Schicksal jüdischer Anwälte in Berlin nach 1933, Berlin 2007.

Curt Riess, Der Mann in der schwarzen Robe. Das Leben des Strafverteidigers Max Alsberg, Hamburg 1965.

Jürgen Taschke (Hg.), Max Alsberg (1877–1933) (= Schriftenreihe Deutsche Strafverteidiger e. V. 40), Baden-Baden 2013.

Max Alsberg, Justizirrtum und Wiederaufnahme, Berlin 1913.

Max Alsberg, Der Prozeß des Sokrates im Lichte moderner Jurisprudenz und Psychologie, Mannheim 1926.

Max Alsberg, Große Prozesse der Weltgeschichte, Berlin 1928.

Max Alsberg, Drama: Voruntersuchung, Berlin 1930.

Max Alsberg, Philosophie der Verteidigung, Mannheim-Berlin-Leipzig 1930.

Max Alsberg (Hg.), Zeitschrift für die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft, Kriminalistische Monatshefte.

Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv Potsdam/Vermögensverwertungsstelle des Oberfinanzpräsidenten Berlin-Brandenburg, Aktenmaterial zu Ellinor Alsberg, geb. Sternberg, Rep. 36A II 595, 596; Rep. 36A Nr. D324, W385, S. 2/3, 4/5, Bericht über die Interessenvertretung und Vermögensverwaltung in den Jahren 1934–1941 vom 5.11.1941.

Bundesamt für zentrale Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen, Berlin, Ref. B1.

Deutsches Biographisches Archiv (DBA), II 22,246-255; III 12,76-108; 1032,170.

Jüdisches Biographisches Archiv (JBA), I 90,306-309; II 19,341-369.

LAB, Wiedergutmachungsakten, B Rep. 025 (A - B) - Wiedergutmachungsämter von Berlin [Buchstabengruppe A - B], 1 WGA 644/49, 4 WGA 821/50, 4 WGA 822/50, 4 WGA 823-826, 1 WGA 1090/50, 5 WGA 1182/50, 43 WGA 1835/55.